Digestive system hormones are the chemical messengers guiding how we break down food, absorb nutrients, regulate appetite, and keep blood sugar steady. If you’ve ever wondered why a small snack sometimes feels surprisingly satisfying—or why some days your stomach seems to set the pace for your energy and mood—these hormones are a big part of the story. Below, I’ve pulled together the most-asked questions, clear explanations, and practical takeaways you can actually use.

So, I was actually just talking to a friend about this—she was complaining that she’s always starving like an hour after lunch, and I realized most people have zero clue what’s actually happening in their stomach. Like, we just think “oh I’m hungry” but there is this massive, invisible chemical conversation going on 24/7 that basically dictates our entire mood.

Gastric hormones: what are they, exactly?

Digestive system hormones are signaling molecules made primarily in the gut and pancreas that coordinate digestion, appetite, motility (how food moves), and metabolic balance. Major players include gastrin, secretin, cholecystokinin (CCK), motilin, ghrelin, peptide YY (PYY), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), somatostatin, and insulin/glucagon from the pancreas.

They don’t act alone; they interact with the nervous system (the gut-brain axis) and your microbiome, fine-tuning digestion in real time. Key idea: hormones rarely work as “on/off” switches. Instead, they rise and fall through your day in response to what and when you eat, your sleep quality, stress levels, and even how much you move.

GI hormones vs gut hormones: is there a difference?

Technically, yeah, but honestly? Nobody really cares in real life. GI hormones refers to the whole tract. Gut hormones usually refers to the intestine stuff that affects hunger.

The main thing is: your gut isn’t just a tube. It’s an endocrine organ. That’s the part most people miss.

How do these hormones support digestion step by step?

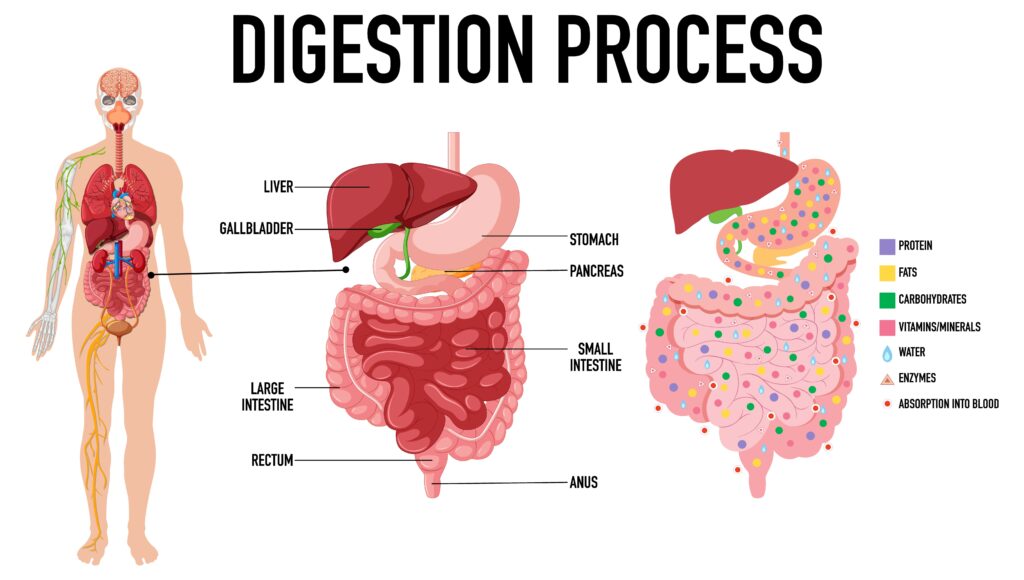

Gastrin: Released in the stomach. Boosts gastric acid to help digest proteins and primes the stomach for incoming food.

Secretin: Released from the small intestine when acidic chyme arrives. Signals the pancreas to release bicarbonate, protecting the intestine and optimizing enzyme function.

Cholecystokinin (CCK): Responds to fat and protein in the small intestine. Triggers bile release from the gallbladder and pancreatic enzymes for fat/protein digestion; contributes to fullness.

Motilin: Coordinates migrating motor complexes between meals—think of it as housekeeping waves that sweep residual food through the GI tract.

Ghrelin: Secreted mostly by the stomach; rises before meals to stimulate appetite and growth hormone release.

Peptide YY (PYY): Released by the ileum and colon after a meal; increases satiety and slows gastric emptying.

GLP-1: Produced in the intestine in response to nutrients; boosts insulin secretion, slows gastric emptying, and promotes fullness.

GIP: Enhances insulin secretion in response to carbohydrates and fats; part of the “incretin effect.”

Somatostatin: A braking signal that suppresses multiple digestive hormones to prevent over-secretion and maintain balance.

Insulin and Glucagon: Pancreatic hormones that regulate blood glucose—insulin helps store and use nutrients after meals; glucagon mobilizes energy between meals. Practical cue: aim for mixed meals (protein + fiber + healthy fat) to engage CCK, PYY, and GLP-1—your natural satiety team.

Which hormone makes me feel hungry – or full?

Hunger: Ghrelin is the pre-meal “go” signal; it rises when your stomach is relatively empty and drops after eating. Poor sleep, irregular meal timing, and high stress can keep ghrelin elevated.

Fullness: PYY, CCK, and GLP-1 create a layered fullness signal that builds 15–30 minutes into a meal and continues for hours, especially with fiber- and protein-rich foods.

Tip: Pause mid-meal for a quick check-in. That 5-minute pause aligns with how satiety hormones catch up, which can prevent overeating.

How do digestive hormones affect blood sugar and energy?

Incretins (GLP-1 and GIP) enhance insulin release when nutrients hit the small intestine, keeping post-meal blood glucose more stable. Slower gastric emptying (via GLP-1 and PYY) spreads out carbohydrate absorption so you avoid rapid spikes and crashes.

Over time, these rhythms influence energy, mood, and cravings. Everyday lever: front-load protein and fiber at meals. For example, start with a salad + grilled fish or legumes before starches. It gently blunts the glucose surge. Further tips in the Hormone Nest’s Supplements for Blood Sugar Control.

Can stress and sleep disrupt digestive system hormones?

Can stress and sleep disrupt gut hormones?

Oh, 100%. You can have the “perfect” diet, but if you’re sleeping 5 hours and stressed to the max? Your hormones will rebel.

Stress = high cortisol = messed up appetite signals.

Bad sleep = high ghrelin (hungry) and low leptin (not full).

It’s not a willpower thing. Your body is literally in survival mode.

So, what foods actually mess with these hormones?

Forget the fancy stuff. Just focus on:

- Protein: Eggs, fish, chicken, beans. Triggers CCK and PYY.

- Fiber: Veggies, oats. Feeds the bacteria that help your hormones.

- Healthy fats: Olive oil, avocado. Stimulates CCK.

- Fermented stuff: Yogurt, sauerkraut. Better bacteria = better signaling.

And honestly? Sometimes you’re just thirsty. Drink some water first.

Are there common symptoms when GI tract hormones are out of balance?

Watch for:

- Hungry right after eating.

- Getting full way too fast.

- Constant bloating.

- Feeling like you need a nap after every meal.

- Late-night cravings that won’t stop.

If that’s you, your hormones are probably trying to tell you something.

How does meal timing change GI hormones?

Consistency is everything.

If you eat at the same time, your ghrelin stays in check. Also, leave 3-4 hours between meals so motilin can do its “housekeeping.” If you graze all day, your gut never gets to clean itself.

Should I consider supplements for hormones in digestion?

They can help, but they aren’t magic. Bitters, ginger, berberine—they’re cool, but talk to a doctor first. Especially if you’re on other meds.

What about GLP-1 medications?

They’re everywhere now. They basically mimic your natural signals to help with appetite. They work, but they work better if you’re still eating protein and staying hydrated. The side effects (like nausea) usually go away once your body adjusts.

So—what’s the deal with the gut-brain axis?

Picture a high-speed gossip line between your gut and your brain, with hormones, nerves, and microbes all spilling the tea. Stress messes with your digestion (you know that), and a chill routine does the opposite. Eating more fiber and fermented foods isn’t just about pooping better—it’s about feeling less cranky, too.

Let’s talk meal timing. Regular meals? They keep hunger hormones from pulling surprise attacks. Eating more earlier in the day? Works for some folks, especially if you want better sleep and energy. Leaving a few hours between meals gives your gut a chance to “sweep up” (motilin at work), which helps with bloat. If late dinners mess with your sleep, try eating earlier for a week. See what happens.

How to build a day that works for your hormones?

Start with a protein-y breakfast—think Greek yogurt with chia, berries, drizzle of olive oil.

Lunch: fiber, protein, fats—maybe a lentil salad with feta and tomatoes.

Dinner: earlier, lighter, lots of colors—grilled fish, roasted veggies, some quinoa.

Snacks? Nuts, edamame, apple with nut butter—small, but packs a punch. Aim for 3–4 hours between meals, walk a bit every day, chill out before you eat.

Near the close, here’s another relevant read at The Hormone Nest that complements these ideas: Cycle Syncing Diet for Hormonal Balance.

When should I see a healthcare professional?

Any red flags—unintentional weight loss, persistent vomiting, blood in stool, significant swallowing difficulty, or severe abdominal pain—warrant medical evaluation. If you have diabetes, PCOS, thyroid disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or you’re on medications that affect appetite or motility, personalized guidance can prevent trial-and-error fatigue.

Feel better? Hungry for lunch yet?

References

- Richter JE, Kumar A. Physiology of gastric acid secretion and gastrin signaling. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544251/

- Holst JJ. The incretin system and its role in glucose homeostasis. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3857600/

- Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5067828/

- Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6161332/

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and does not substitute for personalized medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider with questions about your health or before making changes to your diet, medications, or supplements.